Kidney stones are a common urologic problem that can cause sudden, severe pain and significant disruption to daily life. Understanding the typical symptoms, the biological mechanisms behind stone formation, and the practical steps for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention will help you respond quickly and reduce the chance of recurrence. This guide provides a clear, step-by-step overview based on widely accepted clinical guidance and public-health resources so you can recognize warning signs, understand how clinicians evaluate kidney stones, and follow evidence-based prevention strategies.

Kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) form when dissolved minerals and salts in the urine crystallize and aggregate into solid masses. Stones vary in size from microscopic grains to large, irregularly shaped objects that can block urine flow. Which symptoms appear, how urgently treatment is needed, and which interventions are chosen all depend on stone size, stone location in the urinary tract, the presence of infection, and patient-specific risk factors such as medical history and metabolic differences.

This guide is organized to walk you from initial recognition of symptoms through diagnosis, typical treatment pathways, and practical, medically supported prevention measures. Where relevant, the guide highlights commonly recommended tests and therapies and explains why each approach is used. If you are experiencing severe pain, fever, or blood in the urine, seek urgent medical attention rather than relying on self-care alone.

Because kidney stone care spans emergency treatment, outpatient management, and long-term prevention, the content below is written both for patients who need immediate steps and for people who want to reduce future episodes. Read carefully, keep note of your own symptoms and medical history, and bring this information to your healthcare provider when you consult them.

Recognizing the Symptoms

The most common symptom associated with a stone that is moving through the urinary tract is sudden, intense pain. This pain typically begins in the flank (the area between the ribs and hip) or lower back and often radiates toward the lower abdomen and groin. The pain frequently occurs in waves—sharp peaks that come and go as the ureter muscles spasms around the stone.

Other frequent symptoms include changes in the urine and urinary habits. Patients may notice blood in the urine (hematuria), cloudy or foul-smelling urine, a persistent need to urinate, pain or burning when urinating, or urinating in small amounts. Nausea and vomiting commonly accompany severe pain because of the intense autonomic and visceral response to ureteral obstruction.

Fever and chills are not typical of an uncomplicated stone and instead can indicate a urinary tract infection or an infected obstructing stone, which is a medical emergency. If fever, rigors, or systemic signs of infection occur with obstruction, urgent drainage and antibiotics are often required to prevent sepsis.

Small stones may be entirely asymptomatic and are sometimes found incidentally on imaging done for other reasons. The presence or absence of pain therefore does not rule in or rule out stones—clinical context and diagnostic testing are important.

Common Types and Causes of Kidney Stones

Kidney stones are classified by their chemical composition. The most common types are calcium oxalate stones, followed by calcium phosphate, uric acid, struvite (infection-related), and cystine stones (genetic). Each type forms via different mechanisms and therefore has different risk factors and prevention strategies.

Calcium oxalate stones are the most frequent. They tend to form when urine becomes concentrated or when urine chemistry favors crystallization—for example, high urinary calcium, high urinary oxalate, low urinary citrate, or low urine volume. Diet, certain metabolic disorders, and genetic predisposition all play a role.

Uric acid stones form in persistently acidic urine and are more common in people with gout, those with high-purine diets, or those with dehydrating conditions that concentrate urine. Uric acid stones can sometimes be dissolved medically by alkalinizing the urine.

Struvite stones are associated with recurrent urinary tract infections by bacteria that produce urease. These stones can grow quickly and form large branched shapes that may fill the renal pelvis. They are often managed with both infection control and procedural removal. Cystine stones are rare and result from an inherited disorder causing high cystine levels in the urine.

Who Is at Risk: Key Risk Factors

Several lifestyle and medical risk factors increase the likelihood of developing kidney stones.

- Low fluid intake / dehydration: Concentrated urine increases supersaturation of stone-forming salts. Maintaining higher urine volumes dilutes these salts and reduces stone risk. Clinically, low urine volume is one of the most modifiable risk factors.

- Dietary patterns: Diets high in sodium, excessive animal protein, and high-oxalate foods, with insufficient dietary calcium and produce, can increase stone risk. Excess sodium increases urinary calcium excretion, and excessive animal protein increases urinary uric acid and lowers citrate.

- Medical conditions: Hyperparathyroidism, gout, inflammatory bowel disease, certain urinary tract infections, obesity, and metabolic syndrome are associated with higher risk.

- Family history and genetics: A family history of stones raises your personal risk and can indicate inherited metabolic vulnerabilities, such as cystinuria or hyperoxaluria.

- Certain medications and supplements: High-dose vitamin C, excessive calcium supplements without dietary guidance, some diuretics, and antiretroviral drugs have been linked to increased stone risk in specific contexts.

Addressing modifiable risk factors—especially hydration and dietary choices—is a central part of prevention and long-term management because those measures reduce urinary supersaturation and the chance of recurrence.

Diagnosis: How Clinicians Confirm Kidney Stones

When kidney stones are suspected, clinicians rely on a combination of medical history, physical exam, urine testing, blood tests, and imaging. Urinalysis can reveal blood, signs of infection, or crystals, while blood tests assess kidney function and metabolic abnormalities such as elevated calcium or uric acid. Imaging confirms the presence, size, and location of stones and helps guide treatment decisions.

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis is the most sensitive imaging test and is commonly used in emergency settings because it identifies stones of nearly all compositions and sizes. Ultrasound is commonly used for pregnant patients and for initial evaluation when radiation exposure is a concern; it detects larger stones and hydronephrosis but is less sensitive for small ureteral stones. Plain X-ray (KUB) can detect radiopaque stones such as calcium stones but misses uric acid stones.

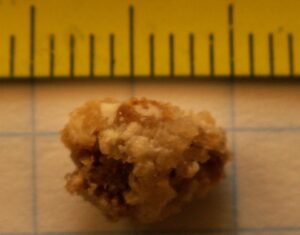

For recurrent stone-formers, clinicians often perform metabolic testing including 24-hour urine collections to measure urine volume, calcium, oxalate, citrate, uric acid, sodium, and pH. These results help tailor prevention (dietary and medical) to the specific stone type and metabolic abnormalities. Stone analysis—when the stone or fragments are available—is very useful for confirming composition and guiding targeted prevention.

Treatment Options: Step-by-Step Decisions

Treatment depends on stone size, location, symptoms, presence of infection, and kidney function. Small stones (usually under 5 mm) frequently pass spontaneously with conservative measures; larger stones or those causing obstruction, persistent pain, bleeding, or infection require active intervention. The main treatment pathways are watchful waiting with medical therapy, pharmacologic stone passage facilitation, shockwave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for large stones.

Below are typical treatment options and when they are used:

- Conservative management / hydration and analgesia: For small stones and stable patients, physicians often recommend increased oral fluids, pain control with NSAIDs as first-line therapy, and antiemetics as needed. In selected cases, medical expulsive therapy with alpha-blockers can be used to relax the ureter and help passage of distal ureteral stones.

- Shockwave lithotripsy (SWL): Non-invasive external ultrasound/stone-targeted shock waves break stones into fragments small enough to pass. SWL is commonly used for kidney stones and proximal ureter stones of limited size and in patients who are good candidates based on anatomy and stone composition.

- Ureteroscopy (URS) with laser lithotripsy: A small scope is passed into the ureter or kidney to visualize and laser-fragment or retrieve stones. URS is preferred for many ureteral stones and has high success rates for stones of various compositions.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL): For very large stones, staghorn calculi, or stones not amenable to less invasive approaches, PCNL creates a small tract through the back into the kidney to remove stones directly.

- Urgent drainage for infected obstruction: When an obstructing stone is accompanied by signs of infection or sepsis, immediate drainage (ureteral stent or percutaneous nephrostomy) and antibiotics are required to control infection and protect kidney function.

Each option has trade-offs: SWL is noninvasive but may require multiple treatments for hard or large stones; URS is minimally invasive with high stone-free rates but requires anesthesia; PCNL is most invasive but most effective for large stone burdens. Stone composition, patient anatomy, and surgical risk guide selection.

Prevention: Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Recurrence

Prevention of recurrent stones focuses on reducing urinary supersaturation of stone-forming compounds through increased fluid intake, dietary modifications, and targeted medications when indicated. Because recurrence rates are high without intervention, individualized strategies based on stone composition and metabolic testing are the most effective.

The following preventive measures are widely recommended:

- Increase daily fluid intake: Aim to produce at least two to 2.5 liters of urine per day (which commonly requires ~2.5–3 liters of fluid intake depending on climate and activity). Higher urine volume dilutes stone-forming solutes and is the single most effective general prevention measure.

- Moderate dietary sodium: High sodium intake raises urinary calcium excretion. Reducing sodium to recommended levels (for many people <2,300 mg/day) can lower urinary calcium and stone risk.

- Maintain normal dietary calcium: Adequate calcium intake from foods (not excessive supplements unless directed) binds dietary oxalate in the gut and reduces oxalate absorption, paradoxically lowering risk of calcium oxalate stones.

- Limit excessive animal protein: Very high animal protein intake increases urinary uric acid and lowers citrate; moderating protein, especially red and processed meats, can help reduce stone formation.

- Address specific metabolic abnormalities: If 24-hour urine testing shows high urinary calcium, high oxalate, low citrate, or persistently acidic urine, clinicians may recommend medications such as thiazide diuretics, potassium citrate, or urinary alkalinization to directly modify urine chemistry.

- Avoid excessive vitamin C supplementation: High-dose vitamin C can increase urinary oxalate in some people, which may contribute to calcium oxalate stone risk.

These measures should be adapted to the individual’s stone type and metabolic testing results. For example, uric acid stone-formers benefit from urine alkalinization and reduced purine intake, while those with infection stones need infection control in addition to removal and prevention strategies.

Pro Tips (Practical Clinical and Self-Care Advice)

1. If you’re experiencing classic renal colic (sudden, severe flank pain), try to note the pattern of pain, any associated urinary symptoms, any fever, and whether oral fluids relieve or worsen symptoms—this information helps clinicians triage urgency.

2. Keep a simple urine log: note daily fluid intake and urine color—aim for pale yellow urine. A sustained darker urine color suggests inadequate daily urine volume and higher recurrence risk.

3. When you pass a stone or fragments, save them in a clean container and bring them to your clinician for composition analysis; results will direct precise prevention measures.

4. If you have metabolic risk factors such as gout, recurrent urinary tract infections, or a family history of early stone disease, request a referral for metabolic evaluation—identifying treatable disorders can significantly reduce recurrence.

5. If you require repeated imaging for stone monitoring, discuss radiation exposure and alternatives (ultrasound or low-dose CT protocols) with your clinician; many centers use low-dose CT for follow-up when necessary.

6. For patients with recurrent infections or large staghorn stones, coordinate care between urology and infectious-disease specialists to ensure both stone removal and durable infection control.

7. If you have an obstructing stone and fever, seek emergency care—infected obstruction is a urologic emergency that may rapidly progress to sepsis.

8. Work with a dietitian experienced in stone prevention when dietary changes are complicated by other medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease) to ensure overall health needs are balanced.

These pro tips combine immediate triage cues and long-term strategies to reduce recurrence and improve outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast will a stone pass?

Stone passage time depends on size and location. Small distal ureteral stones under 5 mm often pass within days to a few weeks with conservative care. Larger stones or proximal stones are less likely to pass spontaneously and may require intervention. Regular follow-up ensures timely escalation of care if passage does not occur or complications develop.

Can diet alone prevent stones?

Dietary and fluid changes substantially reduce risk and are the first-line prevention for most people, but some patients with specific metabolic disorders require medication. A combined approach—diet, fluids, and targeted pharmacotherapy when indicated—provides the best protection for recurrent stone-formers.

Are kidney stones hereditary?

There is a hereditary component for some stone types and metabolic disorders that predispose to stones (e.g., cystinuria, primary hyperoxaluria). Family history raises risk, and clinicians may pursue metabolic testing earlier for patients with a strong family history.

When is surgery unavoidable?

Surgery or endoscopic procedures are chosen when stones are too large to pass, cause uncontrolled pain, produce obstruction with declining renal function, or accompany infection. Choice of procedure—shockwave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, or percutaneous nephrolithotomy—depends on stone size, location, patient anatomy, and clinical urgency.

How are stones analyzed?

Stone analysis is performed by laboratory techniques (such as infrared spectroscopy or X-ray diffraction) on passed stones or retrieved fragments from procedures. The result identifies the dominant composition and guides targeted prevention strategies.

Conclusion

Kidney stones are a common, often painful condition with well-understood causes, recognizable symptoms, and a range of effective treatment and prevention options. Early recognition—especially when severe pain, fever, or blood in the urine occurs—allows prompt evaluation and reduces the risk of complications. Diagnosis typically relies on urine testing, blood tests, and imaging, while treatment choices follow stone size, composition, and clinical urgency. Long-term prevention hinges on individualized strategies grounded in metabolic testing, increased fluid intake, diet modification, and, when appropriate, targeted medications. Working closely with a healthcare team to identify stone type and underlying metabolic or infectious contributors offers the best chance to lower recurrence and maintain kidney health.