Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For IBS Symptoms

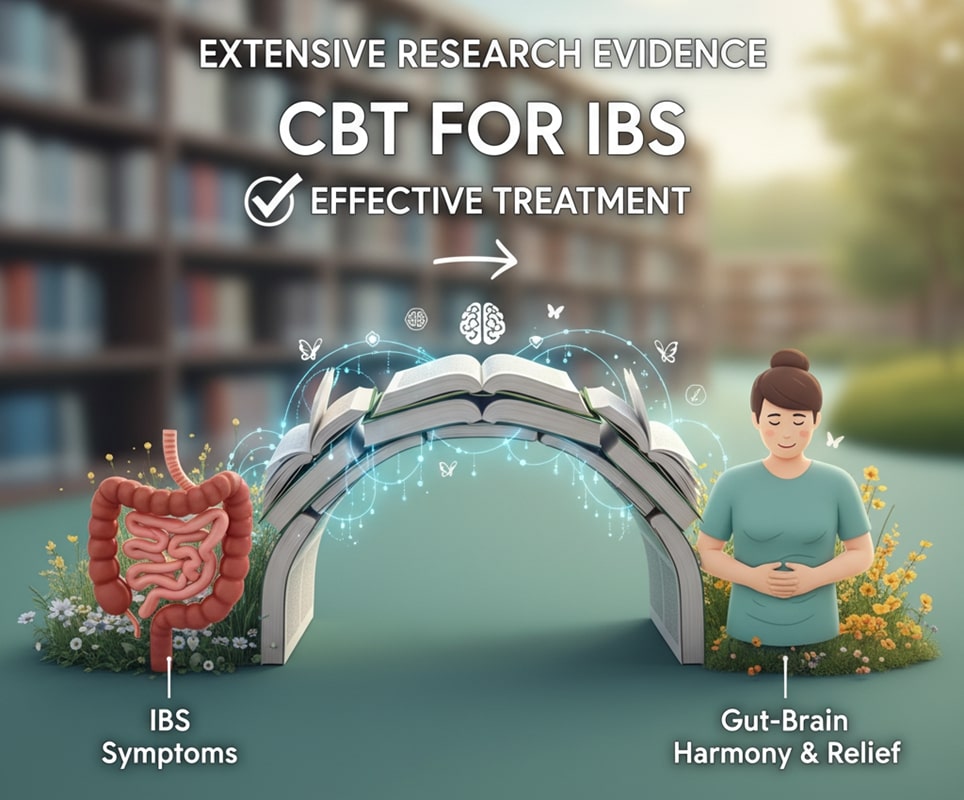

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has emerged as one of the most rigorously tested and clinically effective treatments for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with over 20 published randomized controlled trials demonstrating significant and sustained improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life. Unlike traditional medical approaches that primarily target physical symptoms, CBT addresses the complex bidirectional relationship between the brain and gut, known as the gut-brain axis, which plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms. This therapeutic approach recognizes that IBS is not merely a physical condition but a psychosomatic disorder where psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and maladaptive thought patterns can significantly influence symptom severity and frequency. The integration of CBT into IBS treatment represents a paradigm shift toward holistic care that addresses both the physical and psychological components of this challenging condition.

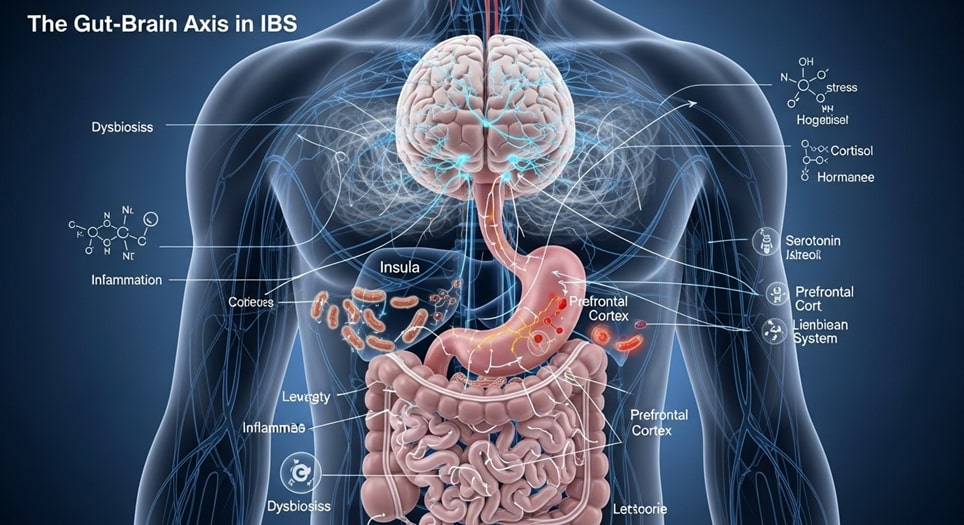

The gut-brain axis represents a sophisticated communication network involving neural, hormonal, and immunological pathways that connect the central nervous system with the enteric nervous system of the gastrointestinal tract. In individuals with IBS, this communication system becomes dysregulated, leading to heightened visceral sensitivity, altered gut motility, and increased inflammatory responses that manifest as the characteristic symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits. CBT works by teaching patients to recognize and modify the psychological triggers that activate this dysregulated gut-brain communication, helping to break the cycle of symptoms and distress that perpetuates IBS. Research has shown that CBT interventions can actually produce measurable changes in brain activity patterns, gut microbiome composition, and inflammatory markers, providing biological evidence for the effectiveness of psychological interventions in treating gastrointestinal conditions.

The effectiveness of CBT for IBS extends beyond symptom management to encompass broader improvements in psychological functioning, including reduced anxiety and depression, enhanced coping skills, and improved self-efficacy in managing chronic illness. Studies consistently demonstrate that patients who receive CBT not only experience significant reductions in IBS symptom severity but also maintain these improvements for extended periods, with benefits lasting at least one year after treatment completion. This durability of treatment effects distinguishes CBT from many medical interventions that may require ongoing medication use or repeated procedures. Furthermore, CBT empowers patients with practical skills and strategies they can apply independently, fostering long-term self-management capabilities that contribute to sustained recovery and improved quality of life.

Understanding the Gut-Brain Connection in IBS

The gut-brain axis represents one of the most complex and fascinating aspects of human physiology, involving intricate communication between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system through multiple pathways including the vagus nerve, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immune mediators, and the gut microbiome. In healthy individuals, this bidirectional communication system maintains optimal digestive function, regulates gut motility, and modulates visceral sensitivity. However, in people with IBS, this communication network becomes dysregulated, leading to a cascade of symptoms that can significantly impact daily functioning. The dysregulation manifests as increased visceral hypersensitivity, meaning that normal digestive processes that would typically go unnoticed become painful or uncomfortable. Additionally, stress signals from the brain can trigger inflammatory responses in the gut, while inflammatory signals from the gut can influence mood, anxiety levels, and pain perception in the brain.

Chronic stress and psychological distress play pivotal roles in perpetuating IBS symptoms through their effects on the gut-brain axis. When the brain perceives stress, whether from external circumstances or internal worry and catastrophic thinking, it activates the sympathetic nervous system and releases stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. These physiological changes directly impact gut function by altering intestinal permeability, disrupting the balance of gut bacteria, slowing or accelerating gut motility, and increasing inflammation in the intestinal wall. The resulting gastrointestinal symptoms create additional stress and anxiety, establishing a vicious cycle where psychological distress exacerbates physical symptoms, which in turn increases psychological distress. This cycle explains why many individuals with IBS notice that their symptoms worsen during periods of high stress, relationship conflicts, work pressures, or major life changes.

Recent research has revealed that the gut microbiome, the trillions of bacteria residing in the digestive tract, serves as a crucial mediator in gut-brain communication and plays a significant role in IBS symptom development and maintenance. The composition and diversity of gut bacteria can influence neurotransmitter production, immune function, and inflammatory responses that directly affect both gut function and brain activity. In individuals with IBS, alterations in gut microbiome composition, known as dysbiosis, have been consistently observed and appear to correlate with symptom severity. Psychological stress can further disrupt the gut microbiome through various mechanisms, including changes in gut motility, alterations in gut pH, and modifications in the production of antimicrobial substances. Understanding these complex interactions helps explain why CBT, which primarily targets psychological factors, can produce measurable improvements in both gut symptoms and the underlying biological processes that contribute to IBS.

The concept of visceral hypersensitivity is central to understanding how psychological factors influence IBS symptoms and why CBT can be so effective in treatment. Visceral hypersensitivity refers to an increased sensitivity to normal digestive processes, where sensations that would typically be imperceptible or mildly noticeable become intensely uncomfortable or painful. This heightened sensitivity develops through complex interactions between peripheral sensory nerves in the gut, spinal cord processing, and brain interpretation of visceral signals. Psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, and catastrophic thinking can amplify these pain signals through a process called central sensitization, where the nervous system becomes increasingly reactive to both painful and non-painful stimuli. CBT addresses visceral hypersensitivity by teaching patients techniques to modify their cognitive and emotional responses to gut sensations, thereby reducing the amplification of pain signals and helping to normalize the perception of digestive processes.

Core Components of CBT for IBS

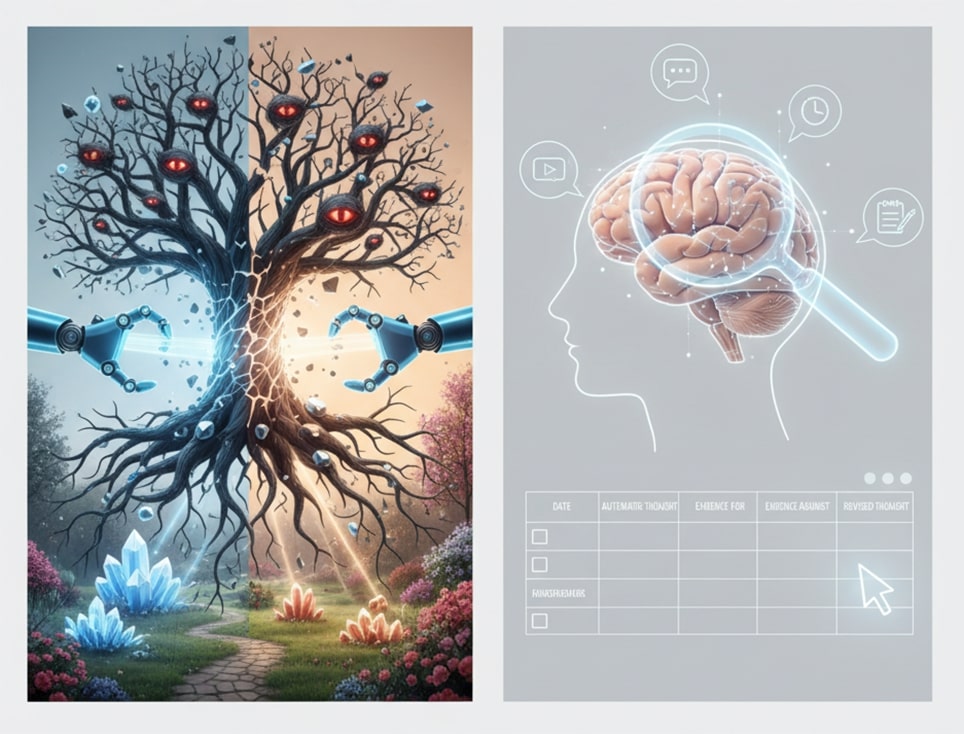

Cognitive restructuring forms the foundation of CBT for IBS, focusing on identifying and modifying the dysfunctional thought patterns and beliefs that contribute to symptom exacerbation and emotional distress. Many individuals with IBS develop maladaptive thinking patterns such as catastrophizing about symptoms, believing that symptoms are unpredictable and uncontrollable, or engaging in “all-or-nothing” thinking about their condition. These cognitive distortions can intensify the stress response and perpetuate the cycle of gut-brain dysfunction. Through cognitive restructuring techniques, patients learn to recognize these automatic thoughts, evaluate their accuracy and helpfulness, and develop more balanced and realistic perspectives about their symptoms and their ability to manage them. For example, a patient who thinks “This pain means something terrible is wrong with me” can learn to reframe this thought as “This is my IBS acting up, and I have strategies to manage it.” This shift in thinking reduces anxiety and stress, which in turn can lead to reduced symptom severity.

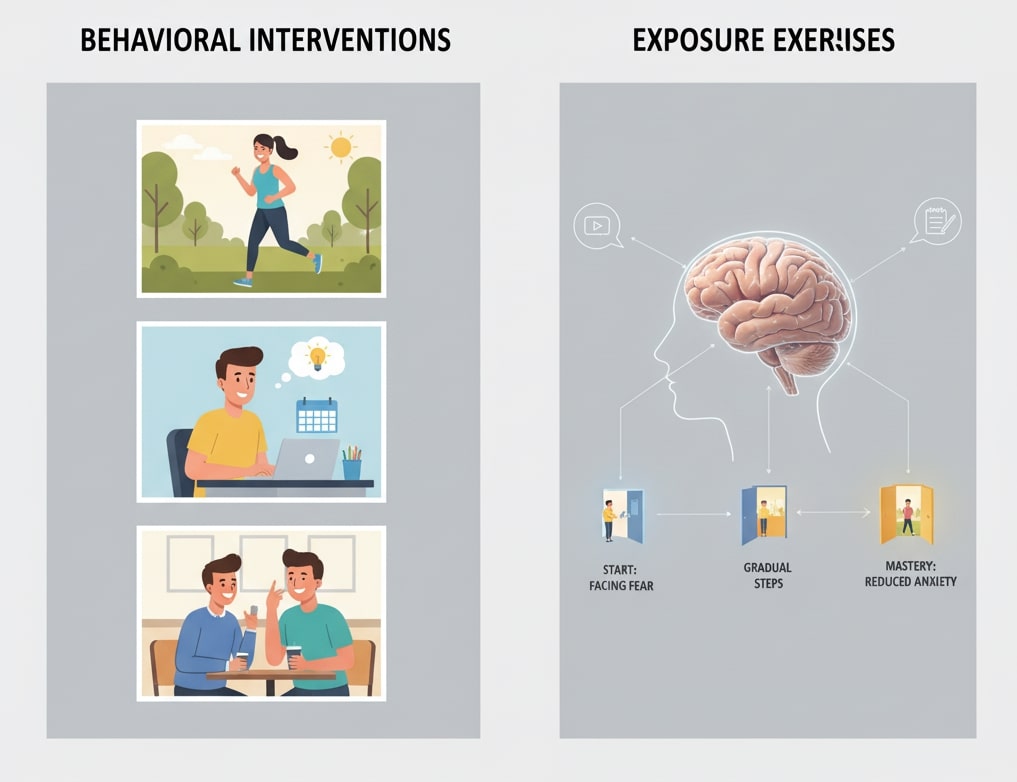

Behavioral interventions in CBT for IBS target specific behaviors and lifestyle patterns that may be contributing to symptom maintenance or exacerbation. Many individuals with IBS develop avoidance behaviors, such as restricting their diet excessively, avoiding social situations where bathrooms might not be readily available, or becoming increasingly sedentary due to fear of symptom flare-ups. While these behaviors may provide short-term relief from anxiety, they often contribute to symptom persistence and reduced quality of life in the long term. CBT helps patients systematically challenge these avoidance behaviors through graded exposure exercises and behavioral experiments. For instance, a patient who has been avoiding certain foods due to fear of symptoms might gradually reintroduce these foods while monitoring their actual symptoms versus their anticipated symptoms, often discovering that their fears were disproportionate to the reality of their experience.

Stress management and relaxation training represent crucial components of CBT for IBS, given the well-established relationship between psychological stress and symptom exacerbation. Patients learn a variety of stress reduction techniques including progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, and guided imagery. These techniques serve multiple purposes: they provide immediate tools for managing acute stress and anxiety, they help interrupt the physiological stress response that can trigger gut symptoms, and they promote overall parasympathetic nervous system activation, which supports healthy digestive function. Regular practice of these techniques can lead to measurable changes in heart rate variability, cortisol levels, and inflammatory markers, providing biological evidence of their effectiveness. Patients are taught to implement these strategies both as daily preventive practices and as acute interventions when they notice early signs of stress or symptom onset.

Problem-solving skills training equips patients with systematic approaches to identifying and addressing the life stressors and challenges that may be contributing to their IBS symptoms. Many individuals with IBS report that their symptoms are closely linked to specific stressors such as work conflicts, relationship problems, financial concerns, or major life transitions. Rather than simply learning to cope with stress, patients develop active problem-solving skills that allow them to address the root causes of stress when possible. The problem-solving process involves clearly defining the problem, brainstorming multiple potential solutions, evaluating the pros and cons of each option, implementing the chosen solution, and evaluating the outcome. This systematic approach helps patients feel more empowered and in control of their circumstances, reducing the sense of helplessness that often accompanies chronic illness and contributing to overall stress reduction.

Activity scheduling and behavioral activation help patients overcome the tendency toward avoidance and withdrawal that often develops in response to chronic IBS symptoms. Many individuals gradually reduce their participation in enjoyable activities, social engagements, and meaningful pursuits due to fear of symptom unpredictability or embarrassment. This withdrawal can lead to increased depression, reduced quality of life, and paradoxically, increased symptom focus and severity. Through systematic activity scheduling, patients gradually increase their engagement in valued activities while learning to manage their symptoms in real-world contexts. This process involves identifying meaningful activities, breaking them down into manageable steps, scheduling specific times for engagement, and problem-solving any obstacles that arise. As patients successfully engage in more activities, they experience improved mood, increased self-confidence, and often find that their symptoms become less prominent in their daily awareness.

Evidence-Based CBT Techniques for IBS Management

Mindfulness-based interventions have emerged as particularly powerful components of CBT for IBS, helping patients develop a different relationship with their symptoms and bodily sensations. Traditional approaches to managing IBS often involve fighting against or trying to suppress symptoms, which can paradoxically increase tension and symptom severity. Mindfulness techniques teach patients to observe their symptoms with curiosity and acceptance rather than resistance, reducing the secondary suffering that comes from fighting against their experience. Body scan meditations help patients develop greater awareness of bodily sensations without immediately interpreting them as threatening, while mindful breathing exercises provide tools for managing acute anxiety and stress. Research has shown that mindfulness-based stress reduction can lead to significant improvements in IBS symptoms, with benefits maintained for at least six months after treatment completion. The practice of mindfulness also helps patients recognize the subtle early warning signs of stress or symptom onset, allowing for earlier intervention and prevention of full symptom flares.

Exposure therapy techniques adapted for IBS help patients gradually confront and overcome the fears and avoidance behaviors that often develop in response to unpredictable symptoms. Many individuals with IBS develop specific phobias related to having symptoms in public places, traveling, eating certain foods, or engaging in physical activities. These fears can become so intense that they significantly restrict the person’s life, leading to social isolation, dietary restrictions, and reduced quality of life. Through systematic desensitization and graded exposure exercises, patients learn to gradually face these feared situations while using coping strategies to manage their anxiety. For example, a patient who fears having symptoms while driving might begin by sitting in a parked car for short periods, then progress to driving around the block, then to longer drives, gradually building confidence and reducing avoidance. The exposure process is always gradual and collaborative, with patients maintaining control over the pace and intensity of challenges.

Cognitive defusion techniques help patients change their relationship with their thoughts about IBS symptoms, recognizing that thoughts are mental events rather than absolute truths or commands that must be obeyed. Many individuals with IBS become entangled with catastrophic thoughts about their symptoms, such as “This pain will never end,” “Everyone will notice if I have symptoms,” or “I can’t handle this anymore.” These thoughts can become so dominant that they drive behavior and emotional responses even when symptoms are mild or manageable. Cognitive defusion techniques, borrowed from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, teach patients to observe these thoughts with psychological distance, perhaps imagining them as leaves floating down a stream or words spoken by a radio that can be turned down. This creates space between the person and their thoughts, reducing the immediate impact of catastrophic thinking and allowing for more flexible responses to symptoms.

Sleep hygiene and circadian rhythm regulation represent important but sometimes overlooked components of comprehensive CBT for IBS. Sleep disturbances are common in individuals with IBS and can contribute to symptom exacerbation through various mechanisms including increased inflammation, dysregulated stress hormones, and impaired gut barrier function. CBT for IBS often includes specific interventions targeting sleep quality, including establishing regular sleep-wake schedules, creating optimal sleep environments, limiting stimulating activities before bedtime, and addressing worry and rumination that can interfere with sleep onset. Patients learn sleep restriction techniques, stimulus control methods, and relaxation strategies specifically designed for bedtime use. Improved sleep quality often leads to improved daytime mood, reduced stress reactivity, and better overall symptom management, creating a positive cycle of improvement across multiple domains of functioning.

Pain coping strategies specifically tailored for visceral pain help patients develop effective responses to abdominal discomfort and cramping that are characteristic of IBS. Unlike other forms of pain, visceral pain from IBS can be particularly distressing because it often feels unpredictable, uncontrollable, and difficult to localize. Patients learn a variety of pain management techniques including distraction strategies, attention modification techniques, and cognitive reappraisal methods. Distraction techniques might involve engaging in absorbing activities, using mental imagery to transport attention away from pain, or practicing counting or word games that require cognitive resources. Attention modification techniques teach patients how to broaden or narrow their focus of attention to minimize pain awareness without completely avoiding bodily sensations. Cognitive reappraisal techniques help patients reinterpret pain sensations in less threatening ways, perhaps viewing them as temporary sensations that will pass rather than signs of serious medical problems.

Step-by-Step CBT Implementation for IBS

Initial Assessment and Goal Setting

The CBT process begins with a comprehensive assessment that examines the patient’s symptom patterns, psychological factors, lifestyle influences, and treatment goals. During this initial phase, the therapist and patient work together to identify specific triggers for IBS symptoms, including stressors, dietary factors, sleep patterns, and emotional states. This assessment goes beyond simply cataloging symptoms to understand the complex relationships between thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and physical sensations that maintain the IBS cycle.

Patients complete detailed symptom diaries that track not only physical symptoms but also concurrent thoughts, emotions, stressors, and behavioral responses. This information helps identify patterns and relationships that may not be immediately obvious to the patient.Goal setting in CBT for IBS involves establishing both symptom-related objectives and broader quality-of-life improvements that the patient hopes to achieve through treatment. Rather than focusing solely on symptom elimination, which may be unrealistic for many individuals with IBS, goals often include reducing symptom severity, improving symptom predictability and controllability, decreasing symptom-related anxiety and distress, and increasing participation in valued activities despite occasional symptoms.

Goals are made specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals), providing clear targets for treatment progress. For example, rather than setting a vague goal of “feeling better,” a patient might set a specific goal of “reducing average daily pain ratings from 7/10 to 4/10 within 8 weeks” or “attending at least two social events per week without canceling due to symptom fears.”The assessment phase also involves psychoeducation about the gut-brain connection, the role of stress in IBS, and the rationale for psychological interventions. Many patients initially feel skeptical about the role of psychological factors in their physical symptoms, particularly if they have been told by others that their symptoms are “all in their head.” Careful explanation of the biological mechanisms underlying gut-brain communication helps patients understand how psychological interventions can produce real, measurable improvements in physical symptoms.

This education reduces stigma and resistance while increasing motivation for engaging in CBT techniques. Patients learn about the bidirectional nature of gut-brain communication, understanding that while stress can influence gut function, gut problems can also influence mood and cognitive function, validating their experience of both physical and emotional aspects of their condition.During the initial sessions, the therapeutic relationship is established as a collaborative partnership where the patient is viewed as the expert on their own experience while the therapist provides specialized knowledge about CBT techniques and IBS management. This collaborative approach is particularly important for individuals with chronic illnesses who may have felt dismissed or misunderstood by healthcare providers in the past. The therapist emphasizes the patient’s strengths, resilience, and existing coping skills while gently identifying areas where additional skills might be helpful. Treatment expectations are discussed realistically, with acknowledgment that improvement often occurs gradually and may involve some ups and downs rather than linear progress. Patients are prepared for the active nature of CBT, understanding that symptom improvement requires consistent practice of new skills and techniques between sessions.

Cognitive Restructuring and Thought Monitoring

The cognitive restructuring phase begins with helping patients develop awareness of their automatic thoughts and cognitive patterns related to IBS symptoms and symptom management. Many individuals with chronic conditions develop habitual ways of thinking about their symptoms that occur so automatically they are barely noticed, yet these thoughts can significantly influence emotional and physiological responses. Patients learn to use thought records or monitoring sheets to capture specific thoughts that occur in response to symptoms, stressful situations, or symptom-related fears. These records include not only the thoughts themselves but also the situations that triggered them, the emotions that followed, the intensity of those emotions, and any behaviors that resulted. This systematic monitoring helps patients recognize patterns in their thinking and begin to see connections between thoughts, emotions, and symptoms.Common cognitive distortions in IBS include catastrophizing about symptom implications, all-or-nothing thinking about symptom control, mind reading about others’ judgments regarding symptoms, fortune telling about future symptom episodes, and personalization of symptom causes. Through the thought monitoring process, patients learn to identify these specific distortions in their own thinking patterns. For example, a patient might discover that they consistently think “Everyone will notice and judge me if I have symptoms in public,” which represents a combination of mind reading and catastrophizing. Or they might recognize thoughts like “If I eat anything other than my safe foods, I’ll definitely have terrible symptoms,” which reflects all-or-nothing thinking and fortune telling. Recognition of these patterns is the first step toward developing more balanced and helpful ways of thinking.Once patients can identify their automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions, they learn techniques for evaluating and challenging these thoughts. This is not about positive thinking or simply replacing negative thoughts with positive ones, but rather about developing more accurate, balanced, and helpful ways of thinking. Patients learn to ask themselves questions such as “What evidence supports this thought? What evidence contradicts it? What would I tell a friend who was having this thought? What’s the worst that could realistically happen? What’s the best that could happen? What’s most likely to happen? How would someone else view this situation?” These questions help patients step back from their automatic thoughts and consider alternative perspectives that may be more accurate and less distressing. The development of balanced, coping-focused thoughts represents the culmination of the cognitive restructuring process. Rather than simply trying to eliminate negative thoughts, patients learn to develop realistic thoughts that acknowledge their challenges while emphasizing their ability to cope and manage their symptoms. For example, the thought “I can’t handle having symptoms at work” might be restructured to “Having symptoms at work would be uncomfortable, but I have strategies to manage them, and I’ve handled difficult situations before.” These new thoughts are not unrealistically positive but rather acknowledge both the reality of the situation and the patient’s capacity to cope. Patients practice generating these balanced thoughts in session and then apply them to real-life situations between sessions, gradually developing new, more helpful thinking habits.

Behavioral Interventions and Exposure Exercises

The behavioral component of CBT for IBS involves systematically addressing the avoidance behaviors and safety behaviors that often develop in response to symptom unpredictability and anxiety. Avoidance behaviors might include restricting social activities, limiting travel, avoiding certain foods despite medical clearance, or consistently staying close to bathrooms. Safety behaviors are subtle forms of avoidance that may include always carrying medications, checking for bathroom locations immediately upon entering new places, or eating very small portions to minimize symptom risk. While these behaviors may provide short-term anxiety relief, they often maintain symptom-related fears and can actually increase sensitivity to symptoms over time.

The behavioral intervention process begins with a detailed assessment of specific avoidance and safety behaviors, helping patients recognize patterns they may not have previously noticed.Graded exposure exercises form the cornerstone of behavioral interventions in CBT for IBS, helping patients gradually confront feared situations while learning that their catastrophic predictions often do not come to pass. The exposure process is always gradual and collaborative, beginning with situations that provoke mild to moderate anxiety and progressively working toward more challenging scenarios. For each exposure exercise, patients and therapists work together to identify specific predictions about what will happen, design behavioral experiments to test these predictions, and then evaluate the actual outcomes compared to the feared outcomes. For example, a patient who fears eating in restaurants might begin by eating a small snack at a quiet café during off-peak hours, then progress to eating larger meals, busier restaurants, and eventually situations that might previously have been completely avoided.Activity pacing and energy management techniques help patients find the optimal balance between staying active and engaged while respecting their body’s needs and limitations.

Many individuals with IBS fall into patterns of “boom and bust” activity, where they push themselves to maintain normal activity levels when feeling well, only to experience significant symptom flares that force them into periods of complete rest and avoidance. This pattern can actually increase symptom unpredictability and severity over time. Patients learn to identify their optimal activity levels, develop realistic daily and weekly schedules that account for symptom variability, and practice consistent pacing that maintains steady engagement without overwhelming their system.

This might involve breaking large tasks into smaller components, alternating between different types of activities, and building in regular rest periods before fatigue or symptoms become overwhelming. Response prevention techniques help patients resist the urge to engage in symptom-focused behaviors that may inadvertently maintain or exacerbate their symptoms. Common symptom-focused behaviors in IBS include frequent body checking or symptom monitoring, repeatedly seeking reassurance from medical professionals or family members, researching symptoms extensively online, or engaging in rituals designed to prevent or minimize symptoms. While these behaviors are understandable responses to symptom uncertainty, they can increase anxiety and symptom awareness, creating a cycle of increased distress and symptom severity. Patients learn to gradually reduce these behaviors while tolerating the anxiety that initially increases when they resist these urges. Alternative behaviors are developed to replace symptom-focused responses, such as engaging in meaningful activities, practicing relaxation techniques, or using distraction strategies when the urge to check or seek reassurance arises.

Stress Management and Relaxation Training

Comprehensive stress management training in CBT for IBS encompasses multiple techniques designed to address both acute stress responses and chronic stress patterns that contribute to symptom maintenance. Patients learn to recognize early warning signs of stress, including physical sensations, emotional changes, cognitive shifts, and behavioral indicators that often precede symptom flares. This early recognition system allows for proactive intervention before stress levels become overwhelming or before the stress-symptom cycle becomes fully activated. The stress management component includes education about the physiology of stress, helping patients understand how stress hormones and nervous system activation directly impact gut function, inflammation, and pain perception.

This understanding helps motivate consistent practice of stress reduction techniques and reduces any sense that stress management is somehow separate from or less important than medical symptom management.Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) represents one of the most well-researched and effective techniques for managing both stress and IBS symptoms. PMR involves systematically tensing and then releasing different muscle groups throughout the body, helping patients develop awareness of physical tension and learn to consciously release that tension. This technique is particularly valuable for IBS patients because it directly addresses the muscle tension that often accompanies symptom flares and anxiety, while also activating the parasympathetic nervous system that supports healthy digestive function.

Patients typically begin by learning PMR in a quiet, comfortable environment and then gradually apply abbreviated versions in real-world situations where they notice tension or early signs of symptom onset. Regular practice of PMR has been shown to reduce not only muscle tension and anxiety but also inflammatory markers and cortisol levels that contribute to IBS symptom severity.Diaphragmatic breathing techniques provide immediate tools for managing acute anxiety and stress while also supporting optimal digestive function through vagus nerve stimulation.

Many individuals with chronic anxiety or IBS develop shallow, chest-based breathing patterns that can maintain sympathetic nervous system activation and contribute to feelings of tension and anxiety. Diaphragmatic breathing involves consciously engaging the diaphragm muscle to create slow, deep breaths that fill the lower lungs and gently expand the abdomen. This type of breathing stimulates the vagus nerve, which plays a crucial role in gut-brain communication and parasympathetic nervous system activation. Patients learn various breathing techniques including 4-7-8 breathing, box breathing, and coherent breathing, practicing these techniques regularly so they become automatic responses during times of stress or symptom onset.

Mindfulness meditation and body awareness practices help patients develop a different relationship with their symptoms and stress responses, moving from reactive patterns toward responsive, conscious choices about how to handle challenging situations. Mindfulness techniques teach patients to observe their thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations with curiosity and acceptance rather than immediately trying to change or eliminate uncomfortable experiences. This approach can be particularly powerful for IBS symptoms, which often trigger immediate anxiety and resistance that can paradoxically intensify the symptoms themselves. Body scan meditations help patients develop greater awareness of physical sensations throughout their body, often revealing patterns of tension or discomfort that they had been unconsciously carrying. Regular mindfulness practice has been shown to reduce symptom severity, improve emotional regulation, and enhance overall quality of life in individuals with IBS, with benefits often maintained long after formal treatment completion.

Long-term Maintenance and Relapse Prevention

The maintenance phase of CBT for IBS focuses on consolidating the skills learned during treatment and developing sustainable strategies for long-term symptom management and continued improvement. This phase recognizes that IBS is often a chronic condition that may require ongoing attention and skill application rather than a problem that can be permanently “solved” through short-term treatment. Patients work with their therapists to identify the techniques and strategies that have been most helpful for their specific situation, creating personalized “toolkits” that can be applied in various situations and circumstances. These toolkits typically include a combination of cognitive strategies for managing symptom-related thoughts and fears, behavioral techniques for maintaining engagement in valued activities, stress management tools for daily use and crisis situations, and problem-solving approaches for addressing new challenges that may arise.Relapse prevention planning involves helping patients anticipate and prepare for potential setbacks or symptom recurrences that may occur in the future.

Rather than viewing symptom flares as failures or signs that treatment hasn’t worked, patients learn to see them as normal parts of managing a chronic condition and opportunities to apply and strengthen their coping skills. The relapse prevention process involves identifying potential high-risk situations such as major life stressors, seasonal changes, work pressures, or relationship challenges that might increase vulnerability to symptom recurrence. For each identified risk factor, patients develop specific action plans that outline early warning signs to watch for, immediate coping strategies to implement, and decisions about when to seek additional support or treatment if needed.Ongoing self-monitoring and skill practice ensure that patients maintain and continue to develop their CBT skills long after formal treatment ends.

This might involve continued use of symptom and mood diaries, regular practice of relaxation techniques, periodic review and application of cognitive restructuring skills, and ongoing engagement in behavioral challenges that prevent the return of avoidance patterns. Many patients find it helpful to schedule regular “check-ins” with themselves, perhaps weekly or monthly, where they review their recent symptom patterns, stress levels, and skill use, making adjustments to their self-care routines as needed. Some patients also benefit from periodic “booster” sessions with their therapist, particularly during times of increased stress or life transitions that might increase symptom vulnerability.Integration of CBT skills with medical care and other aspects of IBS management ensures a comprehensive approach to long-term health and well-being.

Patients learn to communicate effectively with their healthcare providers about both physical symptoms and psychological factors, advocating for integrated care that addresses all aspects of their condition. This might involve sharing information about stress patterns that correlate with symptom flares, discussing the role of psychological interventions in their overall treatment plan, or collaborating with medical providers to optimize the timing and dosing of medications in conjunction with CBT skill use. Patients also learn to integrate their CBT skills with other aspects of their IBS management such as dietary modifications, exercise routines, and sleep hygiene practices, recognizing that optimal symptom management often involves attention to multiple factors rather than relying on any single intervention.

Research Evidence and Clinical Outcomes

Extensive research evidence supports the effectiveness of CBT for IBS, with over 20 published randomized controlled trials demonstrating significant and sustained improvements in symptom severity, quality of life, and psychological well-being. Meta-analyses of these studies consistently show moderate to large effect sizes for CBT interventions, with symptom improvements typically maintained for at least one year after treatment completion. Clinical studies indicate that approximately 70-80% of patients who complete CBT for IBS experience clinically meaningful improvements in their symptoms, with many achieving symptom remission or near-remission. These outcomes compare favorably to medical treatments for IBS, with the added benefit that CBT provides patients with lifelong skills rather than requiring ongoing medication use. The durability of CBT effects is particularly noteworthy, as many medical interventions for IBS require continuous use to maintain benefits.

Recent neuroimaging studies have provided fascinating insights into the biological mechanisms through which CBT produces its therapeutic effects in IBS patients. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that successful CBT treatment is associated with measurable changes in brain activity patterns, particularly in areas involved in pain processing, emotional regulation, and gut-brain communication. These changes include reduced activity in pain-processing regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex and insula, increased activity in prefrontal areas associated with cognitive control and emotional regulation, and improved connectivity between brain regions involved in descending pain modulation. These findings provide compelling evidence that CBT produces real, biological changes in brain function rather than simply helping patients “think differently” about their symptoms.

Emerging research on the gut microbiome has revealed another fascinating mechanism through which CBT may exert its therapeutic effects. Recent studies have shown that successful CBT treatment for IBS is associated with measurable changes in gut bacterial composition, including increases in beneficial bacterial strains and improvements in overall microbiome diversity. These microbiome changes correlate with symptom improvements and may help explain the sustained benefits of CBT treatment. The findings suggest that psychological interventions can influence the gut microbiome through various pathways including stress hormone reduction, improved immune function, and changes in gut motility and secretions that create a more favorable environment for beneficial bacteria. This research represents an exciting frontier in understanding the complex relationships between psychological factors, gut function, and overall health.

Comparative effectiveness research has examined how CBT for IBS compares to other treatment approaches, including medical treatments, dietary interventions, and other psychological therapies. These studies generally show that CBT is at least as effective as medical treatments for IBS, with some evidence suggesting superior long-term outcomes due to the sustained nature of psychological skill acquisition. When CBT is combined with medical treatment, outcomes are often better than either approach alone, suggesting that integrated treatment addressing both physical and psychological aspects of IBS may be optimal. Comparisons with other psychological treatments such as hypnotherapy and mindfulness-based interventions show generally equivalent effectiveness, though individual patients may respond better to different approaches based on their specific symptoms, preferences, and psychological profiles.

Cost-effectiveness analyses have demonstrated that while CBT for IBS may require initial investment in specialized psychological services, it often results in significant healthcare cost savings over time through reduced medical visits, decreased medication use, fewer emergency department visits, and improved work productivity. Studies have shown that the skills learned through CBT enable patients to manage their symptoms more independently, reducing reliance on healthcare services while maintaining or improving symptom control. Additionally, the quality-of-life improvements achieved through CBT often translate into improved work performance, reduced sick leave, and enhanced social and family functioning that provide economic benefits beyond direct healthcare cost savings. These findings support the integration of CBT services into standard IBS care as both clinically effective and economically sound.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Access to qualified CBT therapists represents one of the most significant challenges in implementing psychological treatments for IBS, particularly in rural areas or regions with limited mental health resources. Many therapists lack specialized training in medical conditions or familiarity with the unique aspects of treating IBS, while many gastroenterologists and primary care physicians may not be aware of the evidence supporting psychological interventions for IBS. Addressing this challenge requires increased education of healthcare providers about the role of psychological factors in IBS, expanded training opportunities for therapists interested in medical populations, and development of collaborative care models that integrate psychological services into gastroenterology and primary care settings. Telemedicine and internet-based CBT programs have emerged as promising solutions