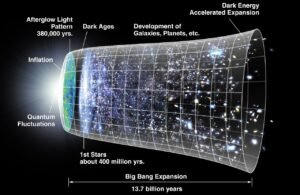

The Big Bang theory stands as the cornerstone of modern cosmology, describing the universe’s origins from a hot, dense state billions of years ago. Despite its widespread acceptance, supported by observations like the cosmic microwave background radiation and the expansion of space, several fundamental issues persist that question its completeness. These challenges arise from discrepancies between theoretical predictions and empirical data, prompting scientists to explore refinements or alternative explanations. This report delves into the most pressing problems, drawing from ongoing research and astronomical observations to highlight where the model falls short.

One of the theory’s strengths is its ability to account for the abundance of light elements like hydrogen and helium, formed in the early universe through nucleosynthesis. However, inconsistencies in other areas, such as the universe’s geometry and the distribution of matter, reveal gaps that require additional mechanisms like cosmic inflation. Inflation, a rapid expansion phase in the universe’s first moments, was proposed to address some of these issues, but it introduces its own complexities and lacks direct confirmation.

As astronomers peer deeper into space with advanced telescopes, new data continues to test the framework. Recent findings from space observatories have amplified debates, suggesting that while the core idea holds, the details demand reevaluation. Understanding these problems not only refines our view of cosmic history but also drives innovation in physics.

Exploring these challenges requires examining historical developments and current evidence. The theory evolved from early 20th-century observations of galactic redshifts, leading to the realization that space itself is expanding. Yet, as measurements improve, anomalies emerge that challenge the standard model.

The Horizon Problem: Uniformity Across Vast Distances

The horizon problem highlights a puzzling uniformity in the cosmic microwave background radiation, the leftover glow from the universe’s early hot phase. This radiation appears almost identical in temperature across the sky, varying by only tiny fractions of a degree. However, regions of the universe separated by billions of light-years should not have had time to interact or equalize temperatures since the beginning, given the finite speed of light.

In the standard model without additional adjustments, distant parts of the cosmos would have evolved independently, leading to expected variations in temperature and density. Observations show otherwise, with the background radiation maintaining a consistent 2.7 Kelvin across vast expanses. This suggests some mechanism allowed these regions to communicate or homogenize early on.

Cosmic inflation offers a potential solution by proposing that the universe expanded exponentially in its first fraction of a second, stretching small, causally connected regions to enormous scales. This rapid growth would make the observable universe appear uniform today. Despite this, direct evidence for inflation remains elusive, relying on indirect inferences from radiation patterns.

Further complicating matters, precise measurements from satellites reveal subtle anisotropies that align with inflationary predictions but also pose questions about the exact timing and duration of this phase. If inflation did not occur uniformly, it could lead to inconsistencies in large-scale structures.

Implications for Causal Connectivity

The issue underscores limitations in our understanding of early cosmic dynamics. Without a way for distant regions to exchange information, the observed homogeneity defies basic relativity principles. Researchers continue to model scenarios where quantum effects or alternative geometries might resolve this without invoking inflation.

Recent data from ground-based experiments at extreme locations, like the South Pole, have searched for signatures of primordial gravitational waves that could confirm inflationary models. So far, these searches have set upper limits but no definitive detections, leaving the problem open to interpretation.

- The cosmic microwave background’s uniformity requires regions beyond each other’s light horizons to share properties, which standard expansion rates cannot explain. This discrepancy points to a need for faster-than-light effective processes in the early universe. Scientists hypothesize that quantum fluctuations amplified during rapid expansion could account for this.

- Observations of galaxy clusters show similar temperature profiles at opposite ends of the sky, reinforcing the problem. These clusters, formed from early density variations, should reflect local conditions, yet they appear synchronized. This suggests a global mechanism at play from the outset.

- Polarization patterns in the radiation provide clues, with straight-line modes observed but swirling patterns predicted by some models absent. This absence challenges simpler inflationary theories, pushing toward more complex variants.

- Large-scale surveys mapping billions of galaxies reveal consistent distribution patterns, incompatible with isolated evolution. Such surveys indicate that the universe’s large-scale structure demands a unifying early event.

- Theoretical simulations without inflation fail to reproduce the observed smoothness, often resulting in patchy universes. Incorporating rapid expansion aligns better with data, but tuning parameters raises questions about naturalness.

- Alternative theories propose varying speed of light in the early cosmos, allowing greater connectivity. While speculative, these ideas aim to avoid fine-tuning issues inherent in standard approaches.

- High-energy particle experiments simulate early conditions, testing if uniformity emerges naturally. Results suggest additional physics beyond known forces may be necessary.

These points illustrate the depth of the horizon issue, emphasizing the need for integrated theories combining gravity and quantum mechanics.

The Flatness Problem: A Finely Tuned Geometry

The flatness problem arises from the universe’s observed geometry, which appears remarkably flat on large scales. In general relativity, the universe’s shape depends on its density compared to a critical value; too high leads to a closed, spherical geometry, too low to an open, hyperbolic one. Measurements indicate the density is extraordinarily close to this critical point, implying a flat cosmos.

Without precise initial conditions, the universe should have deviated significantly from flatness over billions of years due to expansion dynamics. Yet, it remains balanced within one part in a quadrillion, a level of fine-tuning that seems improbable without explanation. This suggests the early universe was set with exquisite precision.

Inflation again provides a mechanism, as the rapid expansion would flatten any initial curvature, much like inflating a balloon smooths its surface. This process drives the density toward the critical value, making the universe appear flat today regardless of starting conditions.

However, the problem persists if inflation’s parameters themselves require tuning. Observers note that while inflation resolves the macroscopic flatness, it shifts the fine-tuning to microscopic scales, prompting debates on whether this truly solves the issue or merely relocates it.

Observational Evidence and Theoretical Implications

Acoustic oscillations in the cosmic microwave background offer precise density measurements, confirming the flat geometry to high accuracy. These sound waves from the early universe imprint patterns that align with a critical density scenario. Deviations would alter these patterns significantly.

Galaxy surveys spanning vast volumes of space show no evidence of curvature, supporting the flat model. If the universe were closed or open, light paths would bend noticeably over cosmic distances, affecting apparent sizes and distributions.

Theoretical models predict that without inflation, the density would evolve away from criticality exponentially, leading to either collapse or empty expansion long ago. The fact that stars and galaxies exist implies conditions were just right for sustained evolution.

Some physicists argue for multiverse scenarios where countless universes exist with varying densities, and we observe a flat one because it’s habitable. This anthropic principle attempts to explain the tuning without additional physics.

- Density measurements from baryonic acoustic oscillations show the universe’s matter content is precisely balanced. This balance prevents rapid collapse or dilution, allowing structure formation. Without it, the cosmos would be inhospitable to life.

- Cosmic triangle tests using distant supernovae confirm flat geometry, as angles sum to 180 degrees over large scales. Curved space would distort these measurements, but data remains consistent with Euclidean rules.

- Inflationary models predict specific curvature signatures in radiation data, which current observations match closely. However, tighter constraints could reveal subtle deviations.

- Alternative gravity theories modify relativity to naturally favor flatness without tuning. These approaches aim to reduce reliance on initial conditions.

- Quantum gravity frameworks, like loop quantum cosmology, suggest bounce scenarios replacing the singularity, potentially leading to inherent flatness.

- Observational limits on curvature are tightening with new surveys, pushing theories to higher precision. Future data may distinguish between inflationary and alternative explanations.

- The problem highlights the interplay between cosmology and particle physics, as early density relates to fundamental constants.

- Simulations of universe evolution under varying densities demonstrate the narrow window for observed structures, underscoring the fine-tuning.

Addressing flatness remains crucial for a complete cosmological model.

The Monopole Problem: Missing Magnetic Monopoles

Grand unified theories, which attempt to merge fundamental forces, predict the existence of magnetic monopoles—particles with a single magnetic pole—produced in the early universe’s high energies. The standard Big Bang model suggests these monopoles should be abundant today, as they are stable and heavy. However, extensive searches have failed to detect any, posing the monopole problem.

If monopoles existed in predicted numbers, they would dominate the universe’s mass, contradicting observed matter density. Their absence implies either the theories are wrong or some process diluted their concentration.

Inflation resolves this by occurring after monopole formation, expanding the universe so vastly that monopoles become extremely rare in the observable region. This dilution makes them undetectable with current technology.

Despite this fix, the lack of monopoles challenges unified theories, as their prediction was a key feature. Ongoing experiments in particle accelerators and cosmic ray detectors continue the hunt, but results remain negative.

Searches and Theoretical Alternatives

Underground detectors designed for rare events have set stringent limits on monopole flux, far below theoretical expectations without dilution. These instruments look for characteristic ionization trails monopoles would leave.

Cosmic ray observations from space-based telescopes search for high-energy signatures, but no candidates have emerged. This non-detection strengthens the case for inflationary dilution.

Some theories propose monopoles decay or are confined, avoiding the problem altogether. Others suggest they exist but interact weakly, evading detection.

The issue connects to the quest for quantum gravity, as monopoles arise in string theory frameworks. Resolving it could unify physics at high energies.

- Predicted monopole masses exceed current accelerator energies, making direct production impossible. Indirect evidence from cosmic relics is sought instead.

- Dilution via inflation reduces density to less than one per observable universe, explaining rarity. This aligns with other inflationary successes.

- Alternative unification models without monopoles are explored, altering force symmetries. These may fit data better without extra assumptions.

- Monopole catalysis of proton decay links to matter stability issues. Limits on decay rates constrain monopole properties.

- Astrophysical bounds from neutron stars and white dwarfs limit monopole accumulation, as they could disrupt stellar evolution.

- Future colliders may probe energies where monopoles form, testing predictions directly.

- The problem illustrates tensions between particle physics and cosmology, requiring consistent frameworks.

The monopole absence continues to puzzle, driving theoretical innovation.

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: The Invisible Dominance

Dark matter and dark energy together comprise over 95 percent of the universe’s energy content, yet their natures remain unknown. Dark matter, inferred from gravitational effects on galaxies and clusters, does not interact with light, making it invisible. Dark energy drives the accelerated expansion, countering gravity on cosmic scales.

The Big Bang model incorporates them as essential components but offers no explanation for their origins or properties. Without understanding these, the theory is incomplete, relying on placeholders for most of the cosmos.

Particle candidates for dark matter, like weakly interacting massive particles, have eluded detection in laboratories. Dark energy might be a cosmological constant or dynamic field, but measurements suggest possible evolution, complicating models.

Recent tensions in expansion rates, known as the Hubble tension, may stem from misunderstandings of dark components. Discrepancies between early and late universe measurements hint at new physics.

Detection Efforts and Challenges

Direct searches for dark matter particles use sensitive detectors buried deep underground to shield from cosmic rays. Despite decades of effort, no confirmed signals have appeared, narrowing candidate parameter space.

Indirect evidence comes from galaxy rotations, where outer stars move faster than visible matter allows, requiring additional gravity from dark halos. Cluster collisions show dark matter separating from gas, confirming its existence.

Dark energy’s effects are seen in supernova distances, showing acceleration since about nine billion years ago. Baryon acoustic oscillations map its influence on large-scale structure.

Modified gravity theories attempt to explain observations without dark matter, but struggle with all data sets. Hybrid approaches combine elements to address shortcomings.

- Dark matter’s gravitational lensing distorts light from distant objects, mapping its distribution. This technique reveals halos around galaxies, essential for structure formation.

- Accelerated expansion implies dark energy’s repulsive force, dominating over matter. Without it, the universe would decelerate, contradicting observations.

- Particle models predict dark matter annihilation signals in dense regions, searched for in gamma rays. No definitive detections yet, but limits guide theory.

- Dark energy’s equation of state parameter measures its behavior; deviations from -1 suggest evolving fields. Current data favors a constant but allows variations.

- Simulations incorporating dark components reproduce observed structures, but without them, galaxies form incorrectly. This validates their necessity.

- Hubble tension, with local measurements higher than CMB inferences, may require dark energy modifications. Resolving it could reveal early universe dynamics.

- Neutrino masses influence dark matter clustering, linking to known particles. Sterile neutrinos are proposed candidates.

- Cosmological surveys aim to pin down dark energy’s evolution, using weak lensing and redshifts. Upcoming missions promise tighter constraints.

These enigmas represent the largest gaps in cosmology.

Baryon Asymmetry: The Matter-Antimatter Imbalance

The universe contains far more matter than antimatter, despite predictions that the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts. Annihilation would leave little matter, yet stars and galaxies exist. This asymmetry requires a violation of symmetry in fundamental laws.

CP violation in weak interactions provides a mechanism, but observed levels are insufficient to explain the imbalance. Additional physics, perhaps from undiscovered particles, is needed.

Early universe conditions, with high temperatures allowing quark-gluon plasma, might have favored matter production. Experiments recreate these to study asymmetry origins.

The problem links to grand unification, where baryon number conservation breaks, allowing proton decay—yet unobserved, setting long lifetimes.

Experimental Insights

Accelerator studies of meson decays measure CP violation, confirming standard model predictions but falling short for cosmic asymmetry. New sources are sought in neutrino oscillations or beyond-standard particles.

Cosmic ray antimatter searches, like positrons and antiprotons, probe primordial residues. Excesses could indicate dark matter annihilations or asymmetry clues.

Theoretical models propose leptogenesis, where lepton asymmetry converts to baryons via sphaleron processes. This ties to neutrino masses.

Resolving asymmetry is key to understanding why the universe is matter-dominated.

Recent Observations: JWST and Early Galaxies

Advanced telescopes have revealed mature galaxies in the early universe, challenging formation timelines. These structures appear fully formed hundreds of millions of years after the origin, sooner than models predict.

Standard scenarios expect gradual assembly from gas clouds, but data shows bright, massive systems with supermassive black holes. This suggests faster evolution or revised understanding of star formation.

While not disproving the core theory, these findings strain galaxy formation models within the framework. Adjustments to feedback processes or initial conditions are proposed.

Ongoing analyses refine galaxy ages and masses, ensuring compatibility. Initial surprises often resolve with deeper study, but persistent anomalies could prompt reevaluation.

Implications for Cosmic Evolution

High-redshift observations push back structure formation, implying efficient processes in dense early conditions. Metal enrichment and dust indicate rapid stellar cycles.

Black hole growth models are tested, as early quasars require seeding mechanisms beyond standard accretion. Mergers or direct collapse are considered.

These discoveries highlight the theory’s adaptability, incorporating new data to refine predictions.

Conclusion

The Big Bang theory, while successful in explaining many cosmic phenomena, faces significant challenges that reveal its incompleteness. Issues like the horizon and flatness problems, the absence of monopoles, the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, the matter-antimatter asymmetry, and recent observational surprises from advanced telescopes all point to the need for deeper understanding. Proposed solutions such as cosmic inflation have helped address some discrepancies, but they introduce new questions and require empirical validation. As research progresses with improved technology and theoretical insights, these unresolved mysteries drive the scientific community toward a more comprehensive model of the universe’s origins and evolution. Ultimately, confronting these problems strengthens our grasp of the cosmos, ensuring cosmology remains a dynamic and evolving field.